Six Weeks TDY

to Hell

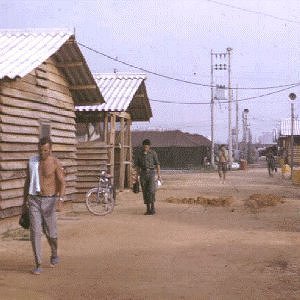

Biên Hòa Air Base was located north of Saigon and near the infamous

LBJ (Long Bien jail), which was the in-country military prison compound

and also a huge munitions storage area. The base itself was upgraded from

an old French post, and still had many of the old French buildings and

small concrete forts scattered around the perimeter. In addition to

the 3rd Tactical Fighter Wing , Army aviation (Chopper) units, ARVAN

units, and various MACV components were on hand.

The actual town of Biên Hòa was situated adjacent to the front gate but

was so infested with Viet Cong that we were not allowed to visit the town

at all. We, the lucky 24 were put up in a long hootch- like

building with typical bunk beds. The facilities were fairly primitive in

that we had to use our helmets as a wash bowl for shaving and bathing. The

bathrooms consisted of a two-hole honey bucket outhouse---and that

was it. We slept fully clothed with our M16s by our side.

The actual town of Biên Hòa was situated adjacent to the front gate but

was so infested with Viet Cong that we were not allowed to visit the town

at all. We, the lucky 24 were put up in a long hootch- like

building with typical bunk beds. The facilities were fairly primitive in

that we had to use our helmets as a wash bowl for shaving and bathing. The

bathrooms consisted of a two-hole honey bucket outhouse---and that

was it. We slept fully clothed with our M16s by our side.

Many of you remember the TV series M*A*S*H

and the episodes about a crazy North Korean pilot who kept trying to bomb

the post. The pilot was called 12 O'clock Charlie. Well, we had

our own version of him named 11 O'clock Charlie at Biên Hòa. Every

night at 11:00 P.M., give or take a few minutes, he would fire off about 5

rockets at the base. But, as opposed to the TV version, 11 O'clock hit

things such as warehouses, barracks, bunkers, and planes.

Ol11 O'clock was joined many

nights, during that fun-loving festival the Vietnamese call Tet, by

friends of his who lobbed mortars at us. They would fire off around 30

rounds and then disappear into the dense jungle surrounding the base, only

to appear the next night at a completely different location. Yet other Charlies

would fire their AK-47s at anything that moved.

Well, this night he was back with a

vengeance shooting rockets seemingly everywhere. One hit about 200 feet

from me this night and I felt a severe stinging feeling in my left leg

below the knee. It was too dark to see and I didn't want to chance using

my flashlight so I waited until I got to the 3rd Air Force dispensary

before asking for help. When I got there, the ground was covered with body

bags and with stretchers of wounded people. I helped move bodies into body

bags and assisted as much as I could with the wounded. This turned into a

full night of holding their hands and talking to them. Anyhow, around

daybreak an overworked medic finally looked at me and said, Did you

know that you've got blood dripping off your boots? With that I took

off my boots and rolled my pants legs up. There were three shrapnel wounds

on my lower leg, none very deep and definitely not life threatening. So,

the medic coats me with some iodine (?), applies a couple of bandages, and

tells me to take it easy.

Later on, at Biên Hòa, I was wounded again.

Once more it wasn serious, and I simply used my bandage pack to wrap

it up and proceeded to forget about the little scratch on my left arm.

One of the most distinct memories I have of

that time was what happened the morning following the long night whenever

a hootch or barracks was hit. Bulldozers and trucks would appear and

within a span of a few hours, wah-lah---we had a new parking lot.

When I finally returned to Phan Rang in mid-March, I think there were more

parking lots than there were hootches or vehicles left.

We were being shelled particularly heavy

one night about 0300 hours, and I was walking a beat near the

Officer's trailers. A rocket landed fairly nearby, and being afraid (if

you weren't, you had to be nuts) I ran for the nearest bunker situated

next to some hootches. The bunker (which basically was four-walls of

overlapping sandbags and PSP roof with more sandbags stacked on top) was

crammed full, and so I stepped back and peered around for another one. A

nice guy, whom Id never met, said, Come on in here, well make

room for you. The place was so packed, however, that I decided to take

my chance down the road, about 50 yards, to the next bunker.

I ran about 30 yards or so when a huge

explosion behind me lifted me off my feet and slammed me to the ground.

When I was able to stand, I looked around and the bunker I had just left

had literally disappeared. I ran back to the spot---which is exactly what

it was---and the only thing left was a hole in the ground about 4 feet

deep. Next to where the bunker had been, I noticed an individual lying in

the top bunk of the hootch. The wall had been surgically removed by the

blast,but the bunkbed and person lying in it looked unharmed. Going around

the crater, I tapped the heavy sleeper on the shoulder. Getting no

response, I shoved him trying to awaken him but to no avail. He had died

from shock, so the medics told me later, and had probably never felt a

thing. Death and destruction were our fellow travelers at Biên Hòa.

A few nights later, I was at the main gate,

near Highway 1 that ran to Saigon, when we started taking incoming

fire from outside the gate. That night I had about eight ARVAN police (we

usually called them the White Mice in deference to their white

helmet liners, white armbands and stature---but also to their notorious

heroism). After the first few shots, I started firing back where I saw

muzzle flashes. The white mice ABANDONED me! They ran back into the

base's interior and I never saw them again that night.

My frantic walkie-talkie calls about being

deserted and under-fire finally brought some help, from the Army. They

sent two helicopters, one with a huge spotlight mounted underneath and the

other, much smaller one, with no lights and painted black. They moved much

as you would expect ballet dancers to move---graceful and with purpose.

While the big chopper with the spotlight drew enemy fire, the little

chopper would dance in and out of the shadows pulverizing areas

where enemy muzzle flashes could be seen. This cleanup operation took

place over my head and seemed to last forever. My Duty Officer later told

me that it had been about ten minutes from the time I first called for

help.

Next morning, the daytime Flight (Platoon)

never did recover any bodies, but a lot of blood pools were found.

I mentioned the old French Forts, the kind

everyone saw all over South Vietnam. In a way, those things were a stark

contrasts of national-wills. The French colonialists built permanent

concrete fortresses to-stay, and we were building out of wood and tents.

Anyway, one of my absolute Worst Nights of All was in motion.

I think all of us who were 'in country

and in positions to get shot at have one or two of those memories that you

can recall with ease, and still bothers you 30 years later. Mine started

with an assignment that night to one of the old French mini forts at

the South end of the base. Due to some Intel from a Green Beret unit

up-country, we had seven of us Air Policemen types on hand. The little

forts were round concrete buildings, roughly ten feet in diameter, with a

place for a machine gun in the metal turret at the top of the fort.

There was an open doorway and several firing slits in the walls.

Unfortunately, the doorway faced outward to the outer perimeter. An Air

Police officer, a Captain, had just driven up to the post in his jeep to

refresh our coffee and ammo when all hell broke loose.

Bullets started whizzing around us---the

roar of Bangalore torpedoes cutting up the concertina barbwire in

front of us was deafening. We all dropped whatever we were doing and

started returning fire as fast as we could. The rest is a mis-mash of

memories about seeing comrades and enemy fall and blood and guts

everywhere. We were finally assisted by army helicopter gunships. The next

morning 144 enemy bodies were found, some as close as three feet from the

fort. We lost two men, with 4 others wounded. And me? Not a scratch.

The Stars and Stripes newspaper titled a piece about this action,

The Battle of Biên Hòa.

We were assigned TDY to Biên Hòa almost six

weeks. During that time, I do not remember a single night that didn go

by without mortars or rockets dropping on us, or bullets winging by. The

good part of all of this was that we all returned to Phan Rang intact and

with a much better understanding of what the grunts out in the field

were experiencing all the time.