Vietnam was driving me crazy. I couldn’t let it go -- It wouldn’t let go of me.

I realized if I didn’t get hold of Vietnam -- Vietnam would get hold of me ... forever.

In 1955, at age 11, World War II had ended only nine years earlier. I was a decade away from my war as the news spoke of Dien Binh Phu and the French in a place called Vietnam. That summer my folks bought a new three bedroom house in east Long Beach, CA for $9,000. I was enrolled in the sixth grade at Tincher Elementary School, just around the corner, and met a life-long friend, Dennis Vander Goore. Several years later, I would marry his little sister, who was four years younger than I.

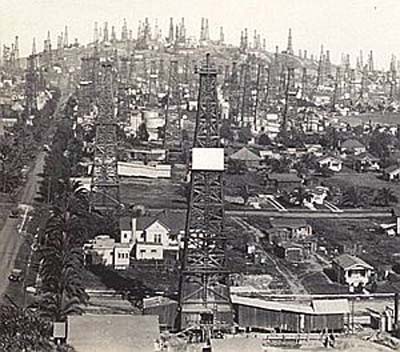

From our new neighborhood, you could see Signal Hill, which is a city in the middle of and completely surrounded by the City of Long Beach. For years the hill was covered in old wooden oil well derricks, and remained so until the great Hancock Oil fire on ‘57. My family attended church at White Temple Baptist in Signal Hill, and if we were lucky, after church dad would drive the old Hudson down Airplane Hill as we were going home. Mom didn’t like Dad to do that because Airplane Hill was more or less a wannabe ski jump. If we four boys were “good” in church, then Dad usually agreed. My mom would say, “Now Eulan…” and that was about as far as she got in discouraging him, but he would always cheerfully reply that he would drive slow.

From our new neighborhood, you could see Signal Hill, which is a city in the middle of and completely surrounded by the City of Long Beach. For years the hill was covered in old wooden oil well derricks, and remained so until the great Hancock Oil fire on ‘57. My family attended church at White Temple Baptist in Signal Hill, and if we were lucky, after church dad would drive the old Hudson down Airplane Hill as we were going home. Mom didn’t like Dad to do that because Airplane Hill was more or less a wannabe ski jump. If we four boys were “good” in church, then Dad usually agreed. My mom would say, “Now Eulan…” and that was about as far as she got in discouraging him, but he would always cheerfully reply that he would drive slow.

The trick about Airplane Hill was that it started out as a shallow drop and then a sudden almost cliff-like drop. You couldn’t see over the cliff until you were committed, and it always felt like you were driving over the edge because you could see Long Beach Airport and the houses 300 feet below. We boys were especially good in church!

In those years, kids could play outside and wander the neighborhood in reasonable safety. My brothers, Ray, Jerry, and Larry, best-friend Dennis and I would build the forerunners to modern skateboards from metal roller skates. We used the skate key and took apart our metal roller skates; nailing front and back to a 2 x 4 board, and “skate boarded” down our sidewalks. We had built plywood ramps and generally raced up and down the block as young boys do. When that got old we would go over to the dry Los Cerritos Flood Control Channel and skate as far as we could down the cement sides.

We needed a new adventure and decided to take our skateboards and race down Airplane Hill. We strapped our skateboards to our backs and rode our bicycles the three miles to envisioned glory. We pushed our bikes up the hillside road staying clear of the middle in case a car came roaring airborne over the top. We had nailed vertical boards to the front of the skateboards to gain sort-of steering control in the direction we hoped to travel. We were all macho and bragging about who would beat whom to the bottom. As we got near the top, it was obvious from a pedestrian’s point of view that Airplane Hill was really steep and really high, and I for one began questioning whose dumb idea it was in the first place.

All of us stared down from the crown of Airplane Hill and watched the ant-like airplanes taking off and landing from the airport, generally putting off what we recognized as a crazy idea -- skateboarding down the hill. After we called each other chicken and pansies, and dared each other, I suddenly gave out my war cry and raced down the road -- Yahooooooooo!

The first thirty yards I still could stand on the board and propel myself forward by kicking with my other foot. But suddenly I felt like I was free-falling and my war cry turned into a genuine death cry! It is a law of nature that immediately at the bottom of every steep road is a stop sign. I rocketed downward surfing the asphalt wave toward the stop sign swerving hard as the skateboard and metal wheels began disintegrating. Showering sparks sprayed the roadside with ball bearings as I was catapulted tumbling into the plowed field beside the road. I stood up, head spinning and surprised to be alive, and shouted in triumph to the wimps still at the top of the road. Suddenly the air was alive with hoots and shouts as all the gang were racing toward the abysm at mach speed with growing alto-screams of terror.

We left our destroyed skateboards in the dirt, and pedaled our bikes home in silence. With bruises and skinned knees, no one ever suggested skateboarding Airplane Hill again.

I never forgot the rush of Airplane Hill, and in 1961 when I was in High School, I would drive my ’51 Chevy to the hill and race over the top – girls screamed and would hold on to you really tight – there were no seat belts back then, and I would lock up my brakes and most always stop at the stop sign.

While growing up at home, I never heard the mention of college. That simply was not in the picture. It was always, “Which service are you going in?” My brother Ray had joined the Navy, and so I decided to join the Air Force. I liked airplanes. So, in 1962, eleven days out of high school, and at 17 years of age, I had joined the Air Force and requested Air Police duty for the purpose of becoming a police officer when my enlistment was up.

As an Air Policeman in 1963, when President Kennedy was assassinated, I was transferred to Bergstrom AFB, Texas to assist with base security when President LBJ returned to Austin from the Washington D.C. Vietnam’s location was still basically unknown to most civilians, but as an AP assigned to do honor guard military funerals for Vietnam KIAs from Texas. Texas still had roadside café’s that didn’t serve blacks, and had water fountains and rest rooms with signs such as “whites” and “colored.” Killed In Action funerals were occurring all too often -- I was well aware of the growing war -- no one in their right mind would want to go to Vietnam.

I decided to volunteer for Vietnam -- I didn't want to miss out on the war -- and in 1965 was transferred to Đà Nẵng, which allowed a short Leave in transit. At home, my brother Jerry had inherited my Chevy, but I managed at least one Airplane Hill ride with a girlfriend. Fun, but not quite the same.

When my year in Vietnam, 1965 to 1966, was over I DEROS’d home. My freedom-bird flight landed at Travis AFB. We were warned about the growing anti-war groups and encouraged to remain on base, and if not to at least wear civilian clothes downtown. After a few days of processing for discharge, my four years tour was up, I was heading for the civilian airport downtown. Airlines gave a flight discount to military in uniform, so I wore my dress blues. A few unfriendly stares, but those were balanced by friendly comments and smiles.

Once airborne, a flight attendant came back to me in coach and said they were bumping me to first-class. I was reseated next to Broderick Crawford whom I recognized as the Hollywood actor having played Chief Dan Mathews in the TV series Highway Patrol. He looked at me and asked, “You just back from Vietnam?” I nodded yes. "Thought so...", and he shook his head in understanding and resumed reading a magazine. He never asked me if I had killed anyone, or any of those questions soon to become too common. He called the flight attendant and asked for two adult beverages. She looked at me and he said that it was all right. She went for the beverages, and I told him it really was all right that I had turned 21 in Vietnam.

The flight was smooth, and after a few sips of an adult beverage, I relaxed a little, and told him I had religiously watched every Highway Patrol series on TV and was a big fan of his. Broderick Crawford nodded, and turned serious and asked me if everyone returning from Vietnam went through Travis AFB. I told him that as far as I knew, the Air Force did, and offered that my tour was up and I was being discharged, and had been at Travis for three days. He asked what I did for those three days, and I told him mostly picking up cigarette butts and CS type jobs waiting processing out. He glowed red in the face and said in that rich baritone voice of his, “You mean they have men coming back from Vietnam picking up cigarette butts?” He was rather upset at that idea.

Landing at LAX in Los Angeles, Broderick Crawford asked if I needed a ride, that he could have his chaffer drop me off anywhere. I told him I was being met by family, and we shook hands and went our own ways. A real gentleman.

A few days after arriving home in Long Beach, I received a phone call from a Colonel who said he was some general’s aide, and wanted to know if it was true I had been assigned clean up policing duties while at Travis AFB. It was, I had told him, and he offered that Broderick Crawford had called a friend, his Congressman in D.C., and both were pissed to no end. The colonel was polite and said that those type details were about to come to a major halt at Travis. He added that Broderick Crawford had served in WWII and saw action at the Battle of the Bulge, and cared about how servicemen are treated. I thanked him, still in my military mind set, and that was that. I have no idea where he got my parents phone number.

My family drove home from LAX on the new 405 San Diego Freeway, which was not there when I joined the Air Force four years earlier. We drove pass Long Beach Airport on the left, and Signal Hill on the right, and I couldn’t help feeling a quickened pulse at seeing Airplane Hill.

My emotions were riding a roller coaster of their own, and I didn’t understand why. Mom cooked a welcome home dinner, and I ate a little but mostly stirred the food around my plate. Mom and Dad seemed concerned and wanted to know what was wrong. Nothing, I would reply, and told them I was tired and wanted to lay down, which I did. I didn’t want to be with them, or anyone. I wanted to go back to Vietnam.

That night I slept for an hour or so and was then wide awake. Vietnam. What are they doing now? I wondered. How’s Blackie doing with his new handler? What post are they on? Have they been mortared yet? Are there flares – of course there are flares. No … it’s day time there now. I got dressed, took Jerry’s car keys and told him not to wake mom that I was going for a drive.

Midnight at Airplane Hill: There were a couple of teenagers parked with lights out and steamed windows. I parked away from them, overlooking Long Beach Airport. Why aren’t I glad to be home? I hated Vietnam … didn’t I? Vietnam: How can I have been there five nights ago, and here now? There’s no war here … no one knows there’s a war over there. I was restless. I got out of the car and leaned against the hood looking down at the airport. I cupped a cigarette so the cherry couldn’t be seen by an enemy 12,000 miles away. To the North, I looked at the blue runway lights, dialed low but still sharp. I thought of where K-9 would be patrolling, and where the perimeter bunkers would be set up and where the mine fields would be. No jungle to clear away. The surrounding fields between the quiet freeway and the runways were blind-dark, and it was easy to image a pop-flare firing at any moment. I thought how fitting, and comfortable, it would be to have a sandbagged bunker where I was standing. I looked South and the miles long beach at night was like Đà Nẵng’s China Beach, ships anchored in the harbor, and amber lights twinkling.

At that moment looking down at the airbase – airport -- the one thing I was certain of was that I wanted nothing to do with firearms and violence. In 1962, eleven days out of high school, and at 17 years of age, I had joined the Air Force and requested Air Police duty for the purpose of becoming a police officer when my enlistment was up. But four years later, Vietnam stood between me and law enforcement: I no longer wanted to be what I had dreamt of becoming -- a police officer.

At dawn, when I could see the dark fields were empty of enemies or friends, I drove home and went to sleep before anyone even knew I had left.

Later that morning, I drove over to see my high school buddy, Dennis. His sister, Kathy, answered the door. Kathy wasn’t Dennis’ little-sister anymore. She called Dennis to the door and we then went for a drive to see some friends. That’s Kathy -- your little sister -- four years younger than us? He grinned, and said, “Yeah … and she’s not married either.” My old high school buddies’ conversations were shallow, as if they were still in high school, and more immature than I had remembered them -- I couldn’t wait to be rid of them.

I bought a ’59 Chevy, with the V-fin trunk lid, painted it a dark metallic cocoa-brown, and had it tuck’n’rolled in TJ Mexico. I wanted to see Kathy again. She had a boyfriend, and I a girlfriend, but we soon started dating. We double-dated a few times and somehow ended up flying over Airplane Hill … girls still screamed and held on tightly.

I stopped seeing Kathy. I stopped seeing anyone. I couldn’t sleep. I found a job and worked all the hours I could to stay occupied and not think of Vietnam. Why was I thinking of that place all the time? I tried talking to Dennis; he had no clue, wanted to know if I had killed anybody. I yelled at him: Yeah I killed fifty and I ate their stinking dead bodies! He looked horrified...then laughed...and then looked uncertain again. I changed the subject. Dennis was quiet, and I understood there would be no one who could understand ... no one to talk with... no one who gave a damn.

Memories of Vietnam were not just memories to me -- Vietnam was real and on every TV daily, and I had friends still there -- but none here -- and I soon learned no one wanted to talk about Vietnam. When my brothers asked, I didn’t want to talk about it. They wouldn’t understand … how could they? No one did. Dennis called. I told him to kiss my ass and hung up -- mom stood in my doorway with her mouth open, and wanted to know if I wanted to pray about it. I closed the door in her face. Seconds later, when I opened it to apologize, she was gone.

Nights were for sleeping. I couldn’t sleep. I didn’t sleep -- nights were full alert. Weeks went by. Reoccurring dreams were vivid versions of all I had seen in Vietnam. Why is this happening? I wondered. Why can’t I sleep? I was in California, but at night my mind didn’t believe it and I would awake with a start as if falling asleep on duty. Vietnam: Sappers; C-130s burning; SSgt Jensen dead; Mortars; Junk piles of twisted aircraft debris; Tent City; Buddhist uprisings; Airmen’s Club; Mortars; Huey choppers; Aircraft bombing the perimeter; Marble Mountain lit up in flares and burning aircraft; F-4 Phantoms’ afterburners rocking bedrock; Freedom Hill with green and red tracers; Battle damaged aircraft; crackling pop flares; Exploding B-57; Truck bed loaded with bodies; Coffins loaded on aircraft; Bodies and wounded in landing Hueys; red tracers; green tracers; Ammo dump firefight; Blackie … always Blackie; K-9 fighting holes; Perimeter Flares; Flare-kickers and pearls of drifting fire; Monsoon rains; Marines; suffocating heat; Mortars; SSgt Kays gone … I wonder if he is dead; Mortars; J.B. dead; Howitzers; rats; You Numba Ten GI; Firefights; Flamethrowers on the perimeter; Bombs falling nearby -- the night was not for sleeping.

Vietnam was driving me crazy. I couldn’t let it go -- it wouldn’t let go of me. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder wasn't in my vocabulary. Shell Shock, Soldier's Heart, all those WWI and II names applied to cowards. I just have to get a grip ... but on what? I had no idea what was happening to me. No one to talk to -- each night a replay of the night before, and the night before that. I realized if I didn’t get a hold of Vietnam -- Vietnam would get a hold of me. I just had to suck it up – right? I didn’t do anything other Airmen hadn’t done in Vietnam, and they’re doing okay … aren’t they? The dreams continued. I told my parents I wanted to go to church with them, and I did. God was there--He didn't want anything to do with me. I couldn't turn it off and no one was there to talk to either.

Airman Gary Knutson DEROS’d to Long Beach. We were from the same city, and assigned Đà Nẵng K-9 together as part of Operation TopDog45. He told me Blackie’s new handler was doing fine. We talked on the phone a couple of times and then he moved. I knew from talking to him that he was beginning to go through whatever it was that I was experiencing.

Airman Gary Eberbach phoned and asked if my invite to visit for a while in Long Beach was still open – it was. He flew in to Long Beach Airport, and had DEROS’d. Gary was also K-9 with me, and seemed his natural happy-go-lucky self. I noticed how dark his tan was, and wondered if I had been like that from Vietnam. And of course he wanted me to set him up with a date. I took him to church. “Church! You gotta be kidding me?” he had protested.

At night, Gary and I talked at times for hours. Vietnam: Remembering K-9 posts; remembering a firefight one night; talking about Blackie and Bucky, about J.B. … everything and anything. Gary couldn’t sleep. Neither could I. I got him a job at Douglas Aircraft with me, and we helped build the first DC-10’s.

The one time I played match-maker and I introduced him to Rita. I figured she could handle him. A match truly made in heaven. I phoned Kathy, and we began talking on the phone -- a lot. We double-dated with Gary and Rita, went to the drive-in movies, to the Cinnamon Cinder and saw Sonny Bono and Cher, and went for drives all over southern California. And Rita and Kathy’s screams were piercing over Airplane Hill.

After nearly a year, Gary and Rita got married, and soon moved to Michigan.

Soon thereafter, my high school phoned and asked if I would address the school's Veterans' Day Assemblies (2,500 students), in uniform (I was already discharged from a four years USAF enlistment). I agreed. A few days later I had parked my car in old familiar stomping-grounds in one of the Millikan High School, Long Beach, student parking lots. I couldn't believe I had agreed to such an idiotic request, and was grumbling to myself while walking toward the auditorium. I didn't have clue-one what I would say, and this was merely the first-assembly with a second-assembly to go! So basically I planned to respond to the Principal's (WWII vet) questions, and somehow get through it.

We stood at the podium as the Principal quieted the assembly who pointed and stared at him and the guy in a blue Air Force uniform. I listened as he introduced me as a graduate of Millikan High School, 1962. Memories of Vietnam were extremely vivid to me at that time in 1967, and, standing at center-stage I looked out at the too-young faces setting in the large auditorium, all quiet and attentive.

The Principal began asking short questions, which I gave clipped answers to. I scanned the balcony for a familiar face – none to be found. The audience, it seemed to me, was embarrassed that I was not at ease and with my too-quiet and too-brief replies. And they were right; my attention was drifting to recent memories. I then ignored a question, took the hand microphone and turned from the Principal to the students directly. I spoke at length of my friend, James B. Jones, who was killed in action at Đà Nẵng in January of 1966, at age 19. The jokes we played on each other ... the trouble we would have gotten into if only the sergeants had found out "who did that!" ... the heat ... the stench, rain and mud and bugs ... the body bags ... and the last night of J.B.'s life at Đà Nẵng Vietnam.

Total silence.

I told the students of how the next morning, still wearing my flack-jacket and helmet and carrying my M-16 weapon, I entered the dispensary where J.B. was carried only hours earlier. Two medics came out of a back room ... is that where he is? -- "I want to see J.B.'s body," I had demanded, but he was not there and had already begun his final journey home.

I tried to make eye contact with students in the front rows, as I told of a letter from Jim's mother and the pain of loss she and his father felt. Was any of what I was saying making sense? I could see that some of the girls were actually crying. The guys, all too close to military age, were setting on seats' edges and listening intently … as I remembered my war in Vietnam.

I asked the "young men" in the auditorium what they would consider important in their lives today, if they "knew their lives could end within a year from today?" I told them that Vietnam was "not a place you would want to go," but at the same time was not a place I regretted going to -- and yet it was impossible for me to explain what that meant or convey "what it was really like" -- but that Vietnam had a life-changing impact on me, and on anyone it touched, in that I could never go back to those days-of-innocence I knew at Millikan High School.

The bell rang signaling end-of-assembly, and usually the teenagers would charge out of the auditorium, as I had done years before, but they remained seated, and quiet. The Principal, who had sat down on a folding chair stood up, shook my hand and thanked me with a quick embrace and pat on the back. My God ... did the Principal that used to threaten to skin me alive just hug me?

The students had not begun to stir, and I noticed the second-assembly students were peeking in the doors to see why they could not yet enter. I walked from the podium toward the wings, and after a few steps the students began to rise, and applaud ... then amazingly, cheer and whistle and shout and the cheering became as loud as if Millikan's football team had just won the State football Championship. I stopped, totally surprised -- shocked really -- and turned to face them. The noise and shouting tapered off to a ripple. I was too choked up to say anything---and what had I said anyway? -- so I just simply popped a salute, held it for a moment, and walked off stage. The cheering and shouts started a new with the balcony students nosily stomping their shoes on the floor.

After second-assembly, some of my old high school teachers came backstage and shook my hand. Some were worried about "the war getting serious." As I left the building through a side door, several students from first and second assemblies were waiting. Some said they had brothers or fathers in Vietnam. One teary eyed girl said that her brother had died in Vietnam, and wanted to know if I had known him.

Years later I would occasionally return to Millikan High School, as a police officer, and always took notice of the Memorial Bulletin Board's growing list of alumni killed in action in Vietnam. The war was still roaring along, with years to go, and the stories of Vietnam veterans being spit on and cursed were now common knowledge.

Later that night, I drove my old ’51 Chevy to the top of Airplane Hill … it was funny that was the one place I felt at peace. And that night I needed time to think. I would always remember my Veterans' Day high school talk, and recognized it for what it really was … my Welcome Home. I also realized Airplane Hill was the one place that felt like Vietnam to me.

I had traded-in my beloved ’59 Chevy for a new Cherokee-140 low-wing airplane. When Kathy and I dated, we took her car. From Long Beach Airport, we flew over to Catalina Island several times and up and down the California coastline at night. We were engaged – and I still needed to get my head screwed on right. The dreams were not as bad, but they were not gone either. Having Gary to talk with had been great. He understood exactly what I felt, and I think talking helped ease him into civilian life. Still, I had decisions to make about the directions my life would take. I inhaled from the cupped cigarette, and smiled to myself, then took a heavy drag with the cherry glowing fire-red in the warm night air -- bright enough to give a sniper a woody. There’s no war here. I am home.

I thought of the one traffic citation I was ever to receive and folded in my pocket. Officers Paul Chastain and Ben Post had stopped me for changing lanes on my motorcycle like an idiot, but before they sent me on my way, we talked for some time. They were good listeners. Officer Chastain asked if I had ever considered joining the police department. The seed was replanted.

That night, as I looked out over the airport’s blue lights … I decided police work was what I really wanted, had always wanted and worked toward, and now what I would commit to. I realized the old saying that you can never go back was true. My old high school friends were too young for me. My new friends would never understand Vietnam. I thought once more of my friends in Vietnam. Somehow, “friends” was too mild a word. It ran deeper than that, and I resolved if ever I could help them I would. Broderick Crawford had known what I was soon to know: the War never will leave you … not for a day … but life was worth living, and the country was worth fighting for, and your comrades – that’s the word – are worth hanging in there for – forever.

Dawn was again approaching. The war-ghosts lingering in the dark fields of mist below evaporated with the California sun, and were nowhere to be seen. The ghosts of my boyhood and wild death cry of tear streaming joy was beckoning for just one more ride over Airplane Hill – and if you listen close, you can still hear the echoes of metal roller-skate wheels, whoops and hoorahs, and screeching tires from innocent boyhood years -- Yahooooooooo!

Post Script: Gary Knutson, Gary Eberbach, and I are members of the Vietnam Security Police Association, Inc., USAF (VSPA.com), and two of the three have Agent Orange VA disabilities. We email often and see each other about once a year. I am still handsome. Both Gary’s look like balding-prunes sucked dry by feeding Wraiths of TV Atlantis fame (heh-heh). Gary and Rita Eberbach have been married nearly 41 years. Kathy and I have been married 41 years this year (2008). My dear friend Dennis passed away in 2007. My brother Ray (US Navy) is a helicopter commercial pilot instructor in Idaho. My brother Jerry (US Army, Vietvet) is in law enforcement in the Palm Springs area. My brother Larry (US Army) is a computer wiz-geek-nerd. I am a retired police sergeant from Long Beach California, and computer programmer/analyst. The students and staff at Millikan High School still remember and honor their veterans to this day, with the Alumni Memorial posted at the campus' main entrance. Signal Hill’s oil derricks were replaced with high-priced condos … but Airplane Hill is still there -- if you dare!

Don Poss

The Thousand Yard Stare is not looking out into the void but inward into the void. Shinning a light into that void may only help one see the ghosts clearer. Someone who walked-the-walk with him must enter the dark and lead or carry him out.