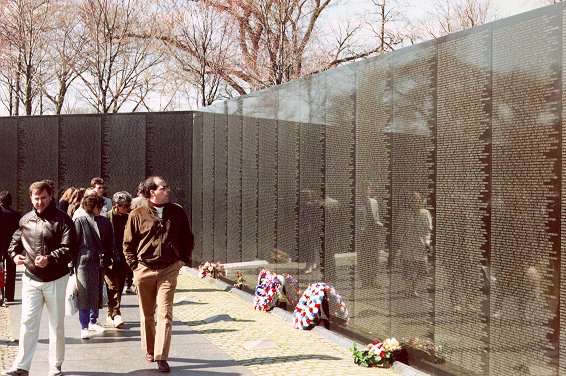

My Wall story begins in 1981 with the announcement of the winning design. Anything but heroic, it looked like a trench, low, dark, brooding, a seemingly endless list of names. It made me angry to look at it. "One more mean spirited jibe at all of us who had served in Vietnam," I thought to myself.

Maybe it was supposed to make me, us, angry. Maybe, Maya Ling Yin, the designer wanted to awaken the voices that were brooding silently; make them open up and reveal their disillusion, their pain, their isolation from the rest of the nation.

A year later I found myself sitting with a group of Veterans. Our leader, Bernie, asked us to talk about the soon-to-be-dedicated national memorial. The room snapped and sparked with quick, intense, responses. I discovered I wasn't the only one who was angry. Bernie had opened a vein. He wisely let the blood flow until it was reduced to a trickle. Then he neatly sutured the wound with a challenge: "If I got a bus how many of you would go to DC to see the memorial dedicated?" Again the room hissed and boomed until Gary, a quiet, short, powerful man whose fierce red beard hid a soft, open face allowed as how, "Maybe we ought to go, take a look, make sure we're right."

If Gary, a tank driver who had been caught in a fierce ambush and forced to watch helplessly as five off his best buddies died, could take it then surely the rest of us could. For the rest of the evening the room buzzed with the earnest talk of planning the trip.

Regrettably, I backed out. I'm not sure why. Maybe survivor's guilt, maybe the fact that I had spent most of my time safely inside a division's base camp, usually far from the battles and the memories that tortured and tormented so many. Or maybe I wasn't ready to let go of my anger, ready to forgive the politicians who deceived me, the fellow students who seemed to take delight in our losses and suffering, the nation which seemed to abandon us while we were in the field. Whatever it was I remained determined to be like that cold black wall in DC: full of history, full of stories, full of feeling and yet holding it all back, waiting for you to come to me, waiting for you to touch, you to listen, you to speak first before I would yield anything I knew, or owned, or felt. The Wall, the nation, wasn't reaching out to me, so I held back and waited.

I used the word 'regrettably' because I made a wrong decision in not going to DC. My fellow vets came back, each one with a story of how The Wall had changed things. The people of the city opened their arms and their hearts to the vets. They were cheered, they were honored, they were respected but more importantly everywhere they went common, ordinary Americans of every description came up to them and said, "Welcome home." The Wall had some sort of magical power that allowed the vets and their fellow citizens to come together and reunite.

I listened to this outpouring of joy and reconciliation but I remained a skeptic. Like Saint Thomas I wanted to see the holes, touch the wounds, before I would allow myself to believe.

It took a good deal of coaxing and gentle nudging by a loving wife. It took a lot of rehearing their Wall Stories in group sessions and while shooting the bull over a few beers with my fellow vets. It took two years of going back and forth with the idea before I could allow myself to say yes. But in 1984 I decided that I would go see The Wall for myself.

So I went. I did it full force without holding back the punches. I went on Veterans' Day, the year they dedicated the statue, three grunts emerging from the jungle to face The Wall and that list of names. I went in my dress greens, wearing the ribbons I had refused to wear in 1968 - 1969, proudly sporting the Big Red One combat patch of the First Infantry Division on my right shoulder.

I began the day at the First Infantry Division's monument, a short walk west from the White House. I was there, standing tall, "at the eleventh

hour, of the eleventh day, of the eleventh month." The division's colors and color guard were present, the division flag snapping in the crisp wind, bristling with battle streamers from Cantigny, France, 1917, to Normandy, 1944, to Highway 13, Vietnam, 1971. The sight of the colors caused my heart to pound and an unexpected shiver run through my body. The ceremony ended with the playing of Taps, by now I was struggling to keep my throat wet and my composure in place.

My wife tells me she was crying through much of this but I was so self absorbed that I only noticed her warm, comforting hand in mine. We left the division's ceremony heading toward my appointment with The Wall.

We crossed Constitution Avenue and reached the long grass of the mall about 50 yards east of the monument. We stood there and watched as a steady stream of vets and their loved ones went by milling about, looking for a place to hear and see the ceremony, or looking for someone from their old unit. I stood back, not quite ready for the full experience, but willing to look on.

I was comfortable.

I was excited.

I was at peace.

"So far, so good." I thought.

President Reagan showed up, said some long overdue words of appreciation, a Commander in Chief who finally got around to thanking those who had served. At last we had a president who was not urging us to, "put Vietnam behind us," like some unspeakable national shame, but to be proud we had served and to remember our fallen brothers and sisters. Then he presented the wreath and moved on.

The crowd cleared out following the speech and I could finally go to the monument itself. I had two names to look for: Doug Knott, a high school friend, and Al Lofton, a fraternity brother who had been killed while I was in Vietnam. I walked up and down The Wall, reading endless names, getting nowhere, growing frustrated.

"Who you looking for?" I heard.

I turned to find a DC area vet. He was thin, with a wide open welcoming face, reading glasses rested on the fat part of his nose, his head topped by a black baseball cap bearing the Vietnam Veterans of America logo. He was slightly stooped, inclining toward the huge book in his hands, patiently seeking to help me break through my shell.

"Doug ..Kn.." I heard my voice squeak. I was shocked to discover the tightness in my throat. I had not been paying attention to my own body. I had not allowed myself to realize that all of this did matter to me and that there was an emotional price yet to be extracted. I caught my breath and started again.

"Doug Knott and Al Lofton."

He began to shift through pages and quickly found both. He gave me the panel and line numbers, pausing to add, "Welcome home," before he turned to help others.I found Doug first. I reached up on the panel and touched his chiseled name.

I hope he knows I remembered. Fairmont High School, Class of 61. A decent, honest, innocent kid. I remember our ninth grade basketball coach looking on in dismay at Doug. He was six foot five, and decently fleshed out, but incapable of pushing others around underneath the basket. Doug loved to play, but winning wasn't necessary to make him happy. He was killed in combat in 1966 and yet I can't imagine him fighting. It simply was not in his nature. Truly he died miscast for the role he had to play.

Al's name was a bit tougher for me to go to. Al was a sharp dresser with the looks of a young Marlon Brando, a slight five o'clock shadow and dark eyes

that darted about excitedly when he was talking. He was outgoing, hard working and popular among the leaders of the house, but he often seemed to me to be brooding. I'm not sure why but we crossed swords early in fraternity life and seemed to always end up in opposing camps. I thought at times it was because he was short and dark while I was tall and fair but it was far deeper felt than that. There were times when I thought he had it in for me and went out of his way to let me know. For now I had to forget our past misunderstandings and rivalry and times when he made me mad or cut me with his remarks. "Hell, he gave as good as he got and so did you. Let it go." I told myself. I hope he understood.

That done I could step outside of my self-absorbed cocoon and see what was going on around me. I heard guys call out, "Don, Don!! It's me, Snoopy, remember?"

"Randy! Semper Fi man!"

"Hey, anyone from Second of the Twenty-eighth here?"

Kathy and I walked the length of the monument in both directions several times, silently absorbing the feelings, the sounds, the visions. At some point I realized the magnetic energy of The Wall. I did not want to leave. We watched as guys, sometimes alone, sometimes in twos and threes, would stretch out respectfully on the grass at the top of the monument, their heads hanging just over the edge, above a panel, a slice of time, a buddy's name, and peer into the cool, clear autumn air. They cradled their heads in their crossed arms, their faces etched with hope that they would find that other face they had thought about so much in the years since Nam. At the further ends of The Wall, they would be low enough that they caught you eyeball-to-eyeball. Examining your face to see if you were the one they longed to reunite with that day, the obvious questions plainly visible on their anxious faces:

"Did he make it home?"

"Was he OK?"

"Did he remember too?"

At odd moments you'd see a face light up with thrill, hear a voice call out a name in unabashed joy, watch as they would run the length of The Wall to physically reunite.

I saw guys bear hug one another. I saw guys cry, laugh, point at bald heads or beer guts or both. I saw guys pray. I saw guys stand with arms wrapped around each other for hours, not willing to let the day end apart from their buddy. I saw a group of women vets come by flag snapping in the brisk November wind, faces set in determination, demanding their spot near The Wall. "Good for them," I thought.

And all the time I heard those healing words from my fellow vets, "Welcome home bro."

The sun began to drop close to the horizon casting long black shadows across the grass, bathing the entire scene in an eerie golden light. I stood at the base of the monument, the deepest spot, and let the experience lap over me, baptize me in it's healing waves. I felt better. I felt closer to home. I felt strong enough to come back to this Wall again. I felt my heart loosen its grip on worthless anger.

Then for some inexplicable reason I walked over to the statue for a closer look. I felt a tug on my sleeve. I turned and saw the distressed face of a new found friend, Steve Slattery. Until that very moment the only thing we had in common was the fraternity of Vietnam and the First Infantry Patch I wore.

"I'm sorry." Steve gasped, "Can you help me out here?" And with that I saw the first tears appear in his eyes. I reached out and held him in my arms. I felt his chest heave in and out, heard the sobs come up from his guts, felt his pain and sorrow. Then I felt my own tears come rushing to my eyes and felt my own insides rock with emotions long held back. Finally the demons that had been tormenting him and me were expelled and we stood there, shoulder to shoulder, arms draped about each other, and cried and talked.

Kathy, sensing the importance of the moment, began snapping pictures of the two of us. My eyes noted the Silver Star and the Combat Infantry Man's Badge he wore on his jacket. He explained that he wore the Silver Star to honor the memory of one of his troopers, a young black kid, just short of his discharge, who didn't have to go to the field that day but volunteered when Capt'n Slats asked. Before the day was over Steve's troop had rescued their sister unit from an ambush, loosing two platoon leaders and Donald Russell Long, the volunteer, who threw himself on a grenade saving Captain Slattery and others in the process. It was Steve's first taste of combat. My losses seemed shallow in comparison but I talked to him about Al and Doug and the other names I visited on my vigil. Steve listened patiently, letting me know that all loss is just that, loss.The experience had been exhausting. My mind spun with memories. Thoughts,

ideas, names, dates, places, visions ... whirling about, forming a mental collage of my Vietnam experience. Memories I thought buried long years before surfaced as moments of pride and love. Steve could not know it but his cry for help had been for both of us. He had helped me as much, or more, than I helped him. He led me to the depths of those memories, allowing me to say out loud how much my Vietnam experience mattered to me.

TODAY, I'm still not all the way home in my thoughts about Vietnam. I may never be. But I know I'm on the way, headed in the right direction, proud that I served. I still have not made peace with a president and his peers who turned their collective backs on the Vietnam war and on Vietnam vets.

I'm still not at peace with a government that does not want to keep its commitments to veterans. I still fear that a total volunteer force will cause our nation

to forget the obligations and responsibilities of a free people to equally share the cost of defending their inheritance. However, I now realize that those angers can disappear or multiply in the shift of a single news day or the results of an election. It's just a part of being in a democracy, accepting the good with the bad inherent in the system and of believing in something, caring, and then doing your part to stay informed and vote, knowing that we have a system where people can make a difference.

But, my concerns about The Wall have been dispelled. No matter what the artistic merits, or demerits, of The Wall, it is clear to me that it works. Perhaps it is because of genius and vision. The genius of Maya Ying Lin, the oriental-Ivy League-non-veteran, designer who I dismissed in anger. The vision of the committee of veterans who chose her design and whom I thought had lost touch with the rest of us. Together they have pulled this whole miracle off. They have found a magical solution that allows this nation's sons and daughters of Vietnam to find peace in their own hearts, pride in their service and thus begin the long journey to reconciliation with the rest of the nation.

I'm not sure why it works. How can black granite, angled slabs, lists of names, all deliberately below ground level, elevate doubting, confused minds? Pull a generation back together? Heal those who have suffered unimaginable pains? Bring us all to some important understanding of the costs of democracy's decisions? Perhaps it is because The Wall has compelled us to help each other come home, veteran and non veteran, soldier and protester, arm-in-arm as Americans on this sacred piece of ground. Perhaps it is because, like me, other veterans have allowed The Wall to open up the doors they have held closed for so long. The reason doesn't matter. The reality of a healing wall does.