John Gertsch

"In all, John was awarded one CIB, one Air Medal, four Army Commendation Medals, three Bronze Stars, two Silver Stars, three Purple Hearts, and for his gallantry on July 19th John was awarded the nation’s highest honor, the Congressional Medal of Honor."

(PhotoLeft: John Gertsch photo provided by Stan Parker.)

In November of 1968, I was walking slack for a recon team called “Tiger Force,” in the jungles of the Central Highlands about 50 miles west of Hue. John Gertsch was walking-point that day, when we came across a well-used trail. Gertsch stopped and put his left fist up, which meant that everyone should stop and be perfectly quiet. Then he spread his hand out in an open gesture, which meant spread out, get down and pay attention. We did. Gertsch and I checked the trail for traps and other signs. We found fresh prints and reported back to the lieutenant, who told us to set up an ambush. Within 15 minutes, a small patrol of six NVA appeared on the trail. We waited until they were in the right spot, made sure there were no more NVA behind them and the opened fire. Afterwards, we cleared the trail, cleaned up any evidence that we were there and left the area. One of the NVA soldiers, an officer, was carrying maps and paperwork. We walked to a suitable site and called in a helicopter to take the NVA paperwork to the rear to be analyzed.

We hiked for another hour and set up a night defensive position. Early in the evening, Gertsch, Zeke, Campos and I, quietly discussed the day’s events before taking our defensive positions. As I sat in silence, just listening to the jungle, I reflected back on just how I got to be in Tigers.I was the second of nine children, four of which were draft age in 1967. The oldest was in the Marines already, one was in military school and another was still in high school. I’d just graduated and had no plans for college. Besides, I felt if I went to Vietnam the chances of my brothers going too would be slim. It worked, I went and everybody else stayed home.I arrived in Biên Hòa, Vietnam, on April 4, 1968, and spent a month or so in additional training in the 90th replacement. After training, I flew north to Camp Eagle where I spent a single night before a few other new guys and I, “cherries” as we were called, were flown by helicopter to fire base Veghel. I spent one hour there and with the rest of the replacements walked into the jungle to meet my company on a hilltop overlooking the Ruong-Ruong Valley. Little did I know that walking through some of the most difficult and remote terrain in South Vietnam would be what I did for the next fourteen months.

(Photo by Bill Lang, KIA 10-08-68: 2 Squad, 2 Platoon, C Co. 1/327/101 1968.)

C Company, 1/327 101st Airborne Division, was a line company of about 180 men with each of us carrying more firepower and equipment than a whole battalion of NVA. The operation was named Nevada Eagle, which consisted of hiking up and down every jungle covered mountain between the South China Sea and the Laotian border; all the while looking for an enemy who was as familiar with this landscape as I was with my backyard at home. Besides, we made so much noise in our pursuit that our location was no secret to anyone. A typical day involved breaking camp, packing our gear, descending the mountain, humping up the next mountain, checking for signs of enemy, and setting up night perimeter. In planning our daily treks, we studied topographical maps, which were drawn from aerial photographs making the terrain appear more like rolling hills rather than the steep and treacherous mountains and valleys under an eighty foot triple canopy we actually encountered. This made the lifers back in their air conditioned mobile homes question our maneuverability, as they had no concept of what the conditions were like in the field. In spite of my reason for being there, I couldn’t help but be in awe of the magnificence of the jungle with its huge plants, ancient trees, pure water, and until we arrived, unspoiled serenity. As a young boy, I was in scouts and loved camping out in the woods of central Missouri. Operation Nevada Eagle and Massachusetts Striker were a scout’s dream of endless camping. Though, I admit it had its drawbacks, as humping a rucksack full of C-rations and chasing Chuck was no picnic.

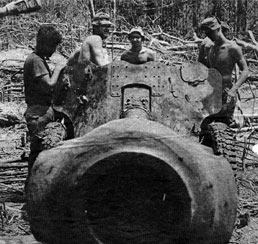

(Photo provided by Roger Morris: 85 Howitzers in the Roung-Roung Valley 1968.)

We were in the jungle only a few weeks when we discovered something that told me how determined our enemy really was. On this day we walked into a natural cathedral fashioned by an eighty-foot canopy covering a 300-yard diameter clearing and surrounded on three sides by a river. In the center of this cathedral, was one of the largest caches of enemy weapons ever found during the Vietnam War. We discovered three Chinese 85- Howitzers, several crew-serviced anti-aircraft guns, hundreds of rifles, mortars, anti-tank weapons and believe it or not – 58 Russian trucks full of equipment. We never discovered how they got all this equipment there, either by river or over land. However, it took a great deal of effort and determination to accomplish that feat.

(Photo by Spec 4 Terry M. McCauley , Stars and Stripes Magazine, April 1968. Caption: "Sorry About That, Charlie - Airborne Infantrymen from divisions' C Co. , 1st Bn. (Abn. ), 327th Inf. test the manevourability of the five enemy 85mm howitzer cannons they captured north of Hue while on reconnosance-in-force operations during Nevada Eagle.")

The top brass didn’t venture into the jungle often, but they came this time to see for themselves what they considered “their” find. Most of us were sent on patrol during this time so that the lifers wouldn’t have to be disturbed by the appearance of soldiers not looking ready for a parade down “Main Street” U.S.A. , as we looked more like General Longstreet’s Confederate soldiers in 1862.

(Photo by Stan Parker: Phil Blevins, John Toberman, Dave Fields and TJ McGinley.)

It was a treat for us to stay in one location for three days, as generally we stayed only over night before moving on. We were told to dig in so I dug the only foxhole in my military career there. It was four feet long and three inches deep. Digging in wasn’t my forte and I felt that learning to be silent and invisible would be better protection. One of the unwritten rules of this particular conflict was, “if you’re not a target, you don’t get shot at. ”In the middle of our second day at this site, a message came around that a friendly unit would penetrate the perimeter in our sector and to be aware. They came out of the jungle like the name implied, silent, intelligent, cautious, deadly--Tiger Force.

(Photo by Stars and Stripes.)

Clad in French camouflage fatigues, boonie hats, and berets, carrying sawed off shotguns and AK47s, NVA belt buckle and bandoleers, these men had a look of people who meant business. They camped with us that night and their quiet confidence and obvious field experience drew me like a magnet. I knew at that moment, that if I were going to spend the next several months in the jungle, I wanted to be with people who knew what they were doing. In the morning, I discovered that Tiger Force had vanished silently into the jungle while we slept.After another month or so of endless humping through the jungle, we arrived at our objective, the northern face of a mountain overlooking the A Shau Valley. This valley was a stretch of land 35 miles long and 8 miles wide with the western end open to the Laotian border.

The NVA used this valley as a major supply route to funnel weapons and supplies, such as we found in the Ruong-Ruong Valley. At certain times during the year, the rains prevented Americans from moving into this valley. The enemy used this time and weather to their advantage. Our objective was to protect a corps of engineers who were planting a minefield across the western entrance to the valley off the Ho Chi Min trail from Laos.On May 1, 1968, we were on a mountain in between Laos and the A Shau Valley. Our commander was Tom Kanain, who had an uncanny ability to look at a topographical map and know where the enemy would be. He told us that getting past the fortifications around the valley would be the most dangerous part of our mission. He was right. On several of the high ridges were semi-permanent NVA complexes both above and below ground. It was between two of these fortifications that my squad was ambushed while on patrol. Within two minutes, nine of the eleven men on patrol were wounded. Only the rear guard and me were not wounded. All the enemy had to do to stop the advance of the Americans was to wound a few of them. Everything would grind to a halt and a hole would be cut in the jungle to accommodate the medevac helicopters. This gave the NVA time to regroup and better prepare for the advancing Americans.

(Photo by Jeff Paige: The A-Shau Valley 1968.)

By the morning of May 3rd, we had worked our way to a point high on a ridge facing north. To the west was the Laotian border, to the east was the wide, open terrain of the valley floor and ahead to the north was a large mountain. The U.S. military name for it was Hill 937, the Vietnamese name for it was Dong Ap Bai, and a year later it was named “Hamburger Hill.” That morning we witnessed a B-52 strike down the center of the A Shau Valley. From our vantage point ten miles away on the ridge, we could not only see, but also feel, the percussion and hear the shrapnel flying through the trees above us. This was quite an experience.The following day, May 4th, helicopters filled the skies to the south of us. The First Cavalry Division was making a helicopter assault into the valley. The sound of gunfire filled the air. Fortunately, we had walked to our position, so we were largely undetected. I never understood the concept of landing large groups of men in helicopters and expecting to maintain an element of surprise.

(Photo provided by Jeff Paige: The A-Shau Valley 1968.) (Photo provided by Jeff Paige: The A-Shau Valley 1968.)

Orders came around for 1/327 to find out if there was any enemy activity on Hill 937. D Company led the way followed by C Company in support. Once on the valley floor, our personal security evaporated. For the first time in months, large groups of men were totally exposed – no canopy, no jungle, no place to hide in this enemy stronghold. Finally, we reached the other side and started our ascent. Then D Company started receiving fire from somewhere in front of us. We encountered reinforced bunkers, heavy machine gun and mortar fire from what seemed like every direction, way more fire power than we’d encountered to date. The object was to find out if there was enemy activity up there, not to take the hill. As soon as we confirmed the hill was occupied, we left. We returned to our sanctuary on the other side via the valley floor where we called in the Air Force to deal with the mountain stronghold. By the time we returned, the entire battalion was on the valley floor protecting the engineers. For the next three hours, jets dropped napalm, 250-pound bombs and what seemed like everything but nukes on this hill with anti-aircraft and green tracers being returned by the NVA. Never have I seen such bold action taken by the enemy as I did that day. This hill was different from all the mountains we had explored so far because of its strategic location, guarding the Laotian border and the entrance to the valley. This audacity by the NVA extended into the night, as we started to receive mortar fire from Hill 937, and artillery fire from somewhere in Laos. We knew we couldn’t stay where we were, as it was getting dark, so we moved. Rarely did Americans move at night, but under the circumstances we had no choice. They knew where we were and had the firepower to reach us. Firefights raged all over the valley that night as encamped Americans were being probed by NVA.Because we were on the move, the enemy didn’t quite know how to deal with us and we were left relatively alone except for the artillery fire that chased us. During this move, we walked through the abandoned Green Beret camp, which was overrun in 1966. As I walked past the crumbling sand bags and the crushed barbed wire, I couldn’t help but believe that this was sacred ground to both the Americans and the NVA. Walking-point was one thing, but walking-point at night through the A Shau Valley in 1968, was something else.

(Photo by Stan Parker / TJ McGinley)

By dawn we reached the southern end of the valley. Exhausted, out of food and low on ammo, but our mission completed, we were extracted the next day. During the stand down after Operation Nevada Eagle, I was approached by a few Tigers, formerly from C Company and asked to join them.

(Photo provided by Stan Parker: Jim Spikes, Raider Rick, Phil Blevins, and Stan Parker.)

It was in this elite group that I first met men who could “out-Indian” the Indians. This recon team consisted of about 40 well-seasoned, hand picked volunteers.

(Photo by Stan Parker:

Tiger Force 1968.)

Only two insignia were found on their uniforms, jump wings and a shoulder scroll with the words Tiger Force – no rank, names or other military insignias was to be found, but one could always tell who was in charge. One of these individual was Staff Sergeant John Gertsch. This man had a great sense of balance between being your friend and your leader at the same time.

(Photo provided by Hank Ortega: John Gertsch.) (Photo provided by Hank Ortega: John Gertsch.)

Under the command of Lt. Fred Raymond, John Gertsch, Dave Fields, and others, Tiger Force worked with a smoothness and efficiency that even surprised the enemy. Gertsch, as he was known, was a master in the field, teaching all who were near the ways of the jungle and how to use it to their advantage. In his words, “how to really be there, but not be there. ” When there was any kind of fighting going on, you could find John diving into it doing what had to be done to get his fellow paratroopers out of danger with no thought for his own safety.John Gertsch was raised in Pittsburgh in the late fifties and sixties. He joined the Army, went to jump school, and was assigned to the 1/327 101st Airborne Division and was sent to Vietnam. After several months in the field with a line company, he was asked to join Tiger Force. This man was absolutely fearless walking-point, a job that I had inherited in my time in a line company. I still had a lot to learn about point, so I started walking slack for John. John was ending his third consecutive tour in Vietnam when he was chosen to represent the 101st Airborne Division at an annual reunion in Ft. Campbell, Kentucky.John knew Tiger Force was headed back into the notorious A Shau Valley and his experience was needed for this dangerous mission. He decided to stay with his unit and help out. As it turned out, that decision was very costly for all of us.Tiger Force was choppered into the A Shau Valley on July 15, 1969, and two days later they were ambushed. The platoon leader was seriously wounded and it was Gertsch who dragged him to a sheltered position. He then assumed command of the heavily engaged platoon and led his men in a fierce counterattack that forced the enemy to withdraw. A short time later, Tigers were attacked again. John charged forward, firing as he advanced. Together John and the other Tigers forced the enemy troops to withdraw and recovered two wounded comrades.Sometime later his platoon came under attack for the third time by a company sized NVA element. John was severely wounded during the onslaught. During the attack, he noticed a medic treating a wounded officer. Realizing that both men were in imminent danger of being killed, John rushed forward and positioned himself between them and the enemy. While the wounded officer was being moved to safety, John was mortally wounded.In all, John was awarded one CIB, one Air Medal, four Army Commendation Medals, three Bronze Stars, two Silver Stars, three Purple Hearts, and for his gallantry on July 19th John was awarded the nation’s highest honor, The Congressional Medal of Honor.That November evening in 1968, sitting in the dark jungle with Gertsch, Campos and Zeke, I didn’t know what the future would bring for any of us. I just knew that I was sitting with the best soldiers and friends I would ever know. I didn’t know I was serving with a true American hero like John Gertsch. It was a great privilege and honor to have served with John. He was the pinnacle of what it meant to an Airborne soldier.

Act well your part. There all honor lies. (Alexander Pope)

T.J. McGinley

Tiger Force

1/327/101 Abn.Div. VN – 68-69

|